The global environment encompasses broad, worldwide environmental factors that are beyond the scope or control of any community or nation:

Atomic bomb detonation; image from James Vaughan at Creative Commons

- Climate change

- Natural disasters

- Mass conflict and violence

- Migration

- Infectious disease

- Natural environment

- Air quality

- Water quality

- Soil quality

Based on a systems approach to health, these factors can overlap and interact in multiple ways with each other and with other major environments described on this site. Climate change, air quality, water quality and soil quality are each discussed on separate pages, while a brief overview of the remaining five topics and their impacts on health follows.

Natural Disasters

Other types of disasters not included in this section

- Wars

- Conflict-related famines

- Diseases and epidemics

Natural disasters include earthquakes, extreme heat or cold, hurricanes, landslides and mudslides, lightning, tornadoes, tsunamis, volcanoes and wildfires.1 In 2015, the human death toll was 22,749 worldwide, with more than 102 million people affected by natural disasters. 2002 disasters impacted the greatest total numbers of humans since the start of the twentieth century: 658,053,168.2

Data from the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters3

Data from the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters4

Health Impacts of Natural Disasters

Human Influence on Natural Disasters

Even though these disasters are caused by natural forces, human activity is having an impact, through emissions that contribute to climate change or by activities such as unconventional gas and oil extraction or clearing land of trees. Evidence is mounting that human activity is influencing the frequency and/or intensity of some types of disasters:5

- Floods

- Droughts, which also contribute to wildfires

- Earthquakes

- Storms, such as hurricanes, which also contribute to landslides and mudslides

- Heat waves

Natural disasters can produce these health impacts, in addition to deaths:6

- Trauma and injury, whether directly from the disaster or secondarily, such as from traffic accidents, loss of access to needed medications such as insulin, loss of power needed for medical equipment or loss of access to medical care

- Increased incidence of communicable diseases including influenza and tuberculosis, plus diseases from contaminated or standing water, including those transmitted by insects. Examples include cholera, typhoid, scabies, trachoma, schistosomiasis, malaria, yellow fever and dengue.

- Increased incidence of heart attacks, asthma attacks and allergic responses

- Aggravation of pre-existing conditions due to stress, such as rheumatoid arthritis

- Malnutrition from lack of access to food through destroyed crops or food stores, or from lack of transportation infrastructure for food

- Food poisoning from the inability to store or cook food appropriately

- Heat- and cold-related injuries from lack of shelter or clothing

- Mental health disturbances

- Increased incidence of conditions related to air pollution, such as particulates produced by fires or added to the air by volcanoes, earthquakes, droughts and other disasters, or by carbon monoxide from inappropriate indoor combustion

- Increased incidence of conditions related to exposures to materials spilled or released during the disaster, including asbestos, fuels, industrial chemicals

- Increased impacts from exposure to mold

Mass Conflict and Violence

Second World War Mortality

Loss of human life from World War II was greater than any other war in history.7 Estimated deaths due to the war:8

- Military: 20 million

- Civilian: 27 million

Global conflict accounted for tens of millions of deaths in the first half of the twentieth century, millions of deaths in the second half of the twentieth century, and more than a half million battle deaths in the first fifteen years of the twenty-first century. One in 10 violent deaths worldwide are from warfare. In 2015, 51 armed conflicts were recorded globally, with almost 100,000 battle deaths.9 In addition to deaths, mass conflict may involve other forms of violence, such as rape and other forms of sexual violence, torture, and forced displacement or labor (slavery).10

Health Impacts from Mass Conflict

Examples of health impacts:12

- Disruptions in medical care, including pregnancy and childbirth care, vaccinations, and treatments for diseases and conditions such as pneumonia, diarrhea, respiratory infections, cancer, kidney disease and diabetes

- Interruptions or destruction of sanitation systems, leading to outbreaks of diseases

- Widespread mental distress, including posttraumatic stress disorder

- Malnutrition or famine, particularly among children

- Trauma and injury leading to permanent disability

- Diseases and health conditions from environmental degradation

- Diseases and health conditions from chemicals and radioactive materials in munitions

image from edin chavez at Creative Commons

Ten-year-old Suleiman, from Dar Al Salam, North Darfur, suffered burns to more than 90 percent of his body when his brother detonated an unexploded device that he found near their house in November 2006. Image from United Nations Photo at Creative Commons.

Migration

People move from their place of birth for many reasons:13

Push Factors

Pull Factors

War

Poverty

Hunger

Environmental or natural disasters

Political instability

Discrimination

Read more : How Many Lumens Do I Need For Outdoor Lighting – Brighten Up Your Yard

Economic depression

Employment opportunities

Political and religious freedom

Study/academic opportunities

Family members

Quality of life

Health Impacts of Migration

A refugee camp in Kanthale, North Eastern Sri Lanka; image from Global Citizen 78 at Creative Commons

Whether mass migrations of economic or conflict refugees or small migrations of individuals or families, migrations impact quality of life and health. The migration process may involve stressors that can impact migrants’ health and well-being. Conditions affecting health in the country of origin and during the journey may include war, torture, loss of relatives, long stays in refugee camps (which may have poor sanitation and overcrowding), imprisonment and socioeconomic hardship. After arriving in the host country, migrants may experience imprisonment, prolonged asylum processes, language barriers, lack of knowledge about health services, loss of social status, discrimination and marginalization.14

Health impacts for refugees are similar to those above related to both natural disasters and mass conflict.

Infectious Disease and Pandemics

Top 10 Countries for Tuberculosis Infection15

IndiaChinaIndonesiaNigeriaSouth AfricaBangladeshEthiopiaPakistanPhilippinesDemocratic Republic of the Congo

Human history holds many examples of widespread disease and death resulting from disease-causing microorganisms—bacteria, parasites, fungi and viruses. Infectious disease was the leading cause of death in the world until the twentieth century16 and still is in low-income countries. Lower respiratory infections, HIV/AIDS, diarrheal diseases, malaria and tuberculosis collectively account for almost one-third of all deaths in these countries.17 Tuberculosis (1.5 million deaths in 2014) and HIV/AIDS (1.2 million deaths in 2014) are the leading infectious disease killers worldwide.18

Interactions of Infectious Disease and Other Environmental Factors

Infectious disease deaths are highly correlated with poverty: The maps of those living on less than two dollars a day and the epidemiology of HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, and many other infectious diseases coincide nearly exactly, although some notable exceptions are seen in Cuba and Kerala State, India.19Nutrition is likewise closely linked with infectious disease, with causality working in both directions: one of the effects of micronutrient deficiencies is increased susceptibility to infection, while parasite infection can lead to malnutrition.20

Interactions between environmental exposures and infectious disease are being studied, such as how toxic chemicals that can undermine the body’s immune response might make individuals more susceptible to certain pathogens.21

Aedes aegypti mosquito; image from Sanofi Pasteur at Creative Commons

Hazardous chemicals and infectious disease can also be related in another significant way. Pesticides, which can impact neurodevelopment and contribute to other health problems, are often used to kill mosquitoes and other vector insects to reduce the spread of infectious disease. To combat mosquitos carrying the Zika virus, whole communities in Brazil, the US and other places have been sprayed with pesticides, potentially increasing exposures among children and pregnant women.22

A further consequence of this pesticide spraying was the deaths of millions of honey bees from spraying in South Carolina.23 Honey bees are essential for pollinating crops and other plants, and thus are critical to human health. With concern about colony collapse disorder already widespread,24 alternatives to pesticide spraying to control infectious disease need to be implemented to protect human and ecological health.

Impacts of Maternal Infections on Fetal and Infant Health

Certain infections in pregnant women can damage the fetus or infant:25

- Congenital cytomegalovirus can impair fetal growth or cause long-term neurological damage or death to infants.

- Herpes simplex virus infection has high mortality and significant morbidity.

- Rubella can cause multiple congenital anomalies including microcephaly, hearing loss and cardiac defects that can result in fetal death.

- Toxoplasmosis can cause intrauterine growth restriction, prematurity and other impacts on the fetus.

- Hepatitis can cause chronic subclinical disease in later childhood or adulthood.

- Syphilis can cause a variety of effects including skin lesions, sensorineural deafness and dental deformities.

- HIV/AIDS leads to progressive immunologic deterioration and opportunistic infections and cancers.

- Zika virus, a recent addition to this list, is associated with microcephaly, with some babies also developing swallowing difficulties, epileptic seizures, bone deformities and vision and hearing problems.

Pandemics

Characteristics of Pandemics26

- Ability to infect, spread rapidly and cause disease in populations of people

- Ability to overload the health care system

- Can come in waves around the globe

- Can disrupt economies and social activities

The worldwide spread of a new disease is called a pandemic. By definition, a pandemic is “an epidemic occurring worldwide, or over a very wide area, crossing international boundaries and usually affecting a large number of people.”27

Influenza

Influenza virus pandemics occur when a new strain of the flu virus emerges before humans can develop immunity to it.28 The past two centuries have seen several major influenza virus pandemics:

- The Spanish Flu (H1N1 strain) of 1918-1919 affected between 20 percent and 40 percent of the world’s population, killing between 20 and 50 million people.

- The Asian Flu (H2N2 strain) of 1957-1958

- Hong Kong Flu (H3N2 strain) of 1968-1969

- the Mexican Flu (H1N1 strain) of 2009, also known as swine flu, affected between 43 and 89 million people and killed between 8,000 and 18,000 people worldwide.29

Seasonal Influenza Facts30

- Influenza viruses can travel around the globe

- Children under two, adults over 65, pregnant women and those with certain medical conditions are most at risk

- Annual flu epidemics are estimated to cause three to five million cases and between 250,000 and 500,000 deaths globally

- The most effective way to protect yourself from getting the seasonal flu is to be vaccinated

There are differences between a pandemic flu and a seasonal flu. The seasonal flu peaks annually in the beginning of the year. Healthy adults have a lower risk of flu-related health effects and may develop immunity from previous exposures, plus there is usually a vaccine available to provide further protection against the seasonal flu virus. A pandemic flu occurs just a few times a century, affecting even healthy people. When two different strains of a seasonal flu virus interact in the same cell within the body, they can combine and make a new strain of the flu, called antigenic shift. This new strain can spread and become a pandemic.31 Annual vaccination can help decrease the opportunity for two flu viruses to interact.

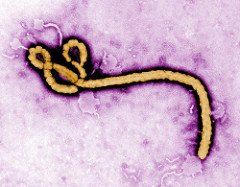

Ebola

Ebola virus, image from CDC Global at Creative Commons

The Ebola virus disease (EVD) surfaced in 1976 and is characterized by an acute, serious illness of fever, fatigue, muscle pain, sore throat and headache, followed by vomiting, diarrhea and, in many cases, bleeding and death. This virus travels from wild animals to humans and then between humans. Typically, EVD has a 50 percent fatality rate overall, although early treatment improves outcomes.32 The most recent outbreak in West Africa, beginning in March 2014, is the largest and most complex Ebola outbreak to date. There have been more cases and deaths in this outbreak than all others combined. It has also spread between countries, both by land and by air travel.33

Smallpox

Smallpox, caused by the Variola virus, has infected humans for thousands of years. Subtype Variola major has a fatality rate of 30 percent. It presents as raised bumps on the face and body accompanied by fever, malaise and sometimes vomiting. A worldwide vaccination program has eradicated the disease, with the last US case reported in 1949 and the last known case in Somalia in 1977. The virus still causes concern for its potential use in bioterrorism.34

Plague

The plague, found globally, is an infectious disease caused by the Yersinia pestis bacteria that can infect humans and certain animals. Contact with bacteria-carrying fleas and direct contact with the body fluids and tissues of infected people can transmit the disease. Although there are three forms, the best known form is the bubonic plague, commonly called the Black Death from its killing of perhaps 50 million Europeans—60 percent of Europe’s population at the time—in the fourteenth century.37

Plague warning in Colorado in 2009; image from Cassandra Turner at Creative Commons

Natural Environment

image from Bureau of Land Management at Creative Commons

The natural environment is our biosphere, the thin layer of living organisms—and everything that supports them—created by our air, water and soil. A healthy natural environment, and access to it, is vital to human health. To support our health, we need to keep our natural environment healthy. To relax our minds, we need to enjoy scenery, greenery and outdoor activities.38

Health Benefits of Natural Environments

Studies have found a wide range of health benefits from living in “greener” environments—those with greater amounts of green space (urban green space, agricultural space, natural green space) in close proximity to people’s homes.39

image from Pimthida at Creative Commons

- People report fewer illness symptoms and have better perceived general health, and this effect is somewhat stronger for lower socioeconomic groups

- Mental health appears to be better

Research with workers, prisoners and postsurgical patients indicates that the ability to see natural environments is associated with better health outcomes. People also gain health benefits from interacting with gardens, owning pets and enjoying wilderness.40 Evidence suggests that simply inhaling the essential oils of trees regularly can reduce anxiety, depression, anger and diseases related to psychosocial stress. Other benefits associated with exposure to nature:41

image from Alaska Region US Fish & Wildlife Service at Creative Commons

- Lower cholesterol and blood pressure

- Stress reduction and a better outlook on life

- Greater longevity

- Reduced burden of mental illness

A healthy natural environment invites walking, which is associated with many positive health outcomes, including a reduction of the impacts of diabetes, asthma, arthritis, cancer and musculoskeletal diseases. Regular walking may even prevent injuries.42 More information about the health effects of active transportation, and how those are influenced by the built environment, is listed on the Built Environment page.

Children and Nature

image from @SunishSebastian at Creative Commons

Research shows a significant association between decreased outdoor activity time, increased time indoors and rising childhood obesity. Federal and state policies have compounded this problem of decreased outdoor time for children by making it harder for children to get outside during the school day, such as by pressuring schools to cancel or reduce recess to prepare for standardized tests.43

A school field trip; image from Nancy Hepp

Policies that limit children’s access to outdoor time seem misguided, for the effects of time in nature include improved cognitive functioning (including increased concentration, greater attention capacities, and higher academic performance), better motor coordination, reduced stress levels, increased social interaction with adults and other children, and improved social skills.44 Children do better in school when they can engage in natural environments. Simply seeing nature from the school room is associated with improved academic outcomes. Research has found that a natural learning environment fosters critical thinking and problem solving, reduces the symptoms of ADHD and increases focus and attention. Using the environment to teach has been shown to increase a child’s enthusiasm for learning, improve impulse control and reduce disruptive behaviors.45

image from William Petruzzo at Creative Commons

Access to a healthy natural environment supports children in other ways. Children of mothers who experienced more nature have shown better fetal growth and healthier birth weights. Children who play in direct sunlight have lower rates of nearsightedness and increased vitamin D levels.46

Information about how access to healthy natural environments interacts with poverty and social factors is on the Cumulative Impacts page.

Reduction of Natural Environments

Practices such as deforestation, air and water pollution, soil degradation and landscape-scale mining and agriculture have become customary. Our use of Earth’s natural resources is not sustainable and is leading to a loss in biodiversity. We are said to be in the sixth mass extinction, one created by human activities. More than 30 percent of all species might be extinct by 2050.47

Facts about humans’ impact on Earth’s resources:48

image from Asian Development Bank at Creative Commons

- We use 60 percent more resources than our planet can produce.

- At this pace, we will need two planet’s worth of resources by 2030.

- As of 2016, 50 countries are experiencing moderate or severe water stress.

- 27 countries are importing more than half of their water.

- Over the last 40 years, we have lost one-third of our global biodiversity.

- Over the last 40 years, humans’ impact on the Earth’s ecosystem has about doubled.

- Today, three-fourths of all humans live in countries that consume more than they replenish.

- Global warming is leading to species extinction.

Nature is a key component of economies yet is often missing from economic accounting. In calculating costs for goods and services, we fail to include the value of natural processes critical to the production of those goods and services. Services provided by intact ecosystems include absorbing and storing rainfall, purifying water, modulating effects of storms and floods, fertilizing soil, cleaning air, producing oxygen, storing carbon, recycling wastes and more. Our economic systems—and human life—would soon collapse without these services, and they must be part of any “bottom line” assessments if those assessments are to be useful and durable. Production that disrupts or impedes natural services by introducing chemicals or radiation, by diverting water, or by overwhelming natral flows of materials or energy must include the costs of these actions to be accurate and sustainable.

The biodiversity of Earth’s species contributes to the discovery of new drugs and technologies that further support health, another factor to be included in accounting systems.49

This page’s content was created by Lorelei Walker, PhD, and Nancy Hepp, and last revised in November 2016.

CHE invites our partners to submit corrections and clarifications to this page. Please include links to research to support your submissions through the comment form on our Contact page.

* header image from Vilma at Creative Commons

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Natural disasters and severe weather. 2014. Viewed October 20, 2016.

- Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. EM-DAT: The International Disasters Database. Viewed October 21, 2016.

- Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. EM-DAT: The International Disasters Database. Viewed October 21, 2016.

- Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. EM-DAT: The International Disasters Database. Viewed October 21, 2016.

- Riebeek H. The rising cost of natural hazards. Earth Observatory. March 28, 2005. Viewed October 22, 2016; Brown D, Cabbage M, McCarthy L. NASA, NOAA Analyses Reveal Record-Shattering Global Warm Temperatures in 2015. National Air and Space Administration. January 20, 2016. Viewed October 22, 2016; US Geological Survey. How large are the earthquakes induced by fluid injection? USGS FAQs. June 15, 2016. Viewed October 22, 2016.

- March G. Natural Disasters and the Impacts on Health. Information Resources: Health, Disasters and Risk. United Nations Office on Disaster Risk Reduction. 2002. Viewed October 21, 2016; Moren-Abat M et al. Climate Change Impacts on the Water Cycle, Resources and Quality. European Commission. 2007. Viewed October 21, 2016.

- Human Security Report Project. The decline in global violence: evidence, explanation, and contestation. Simon Fraser University, Canada. 2013. Viewed October 21, 2016.

- Estimated war dead in World War II. War Chronicle. Viewed October 21, 2016.

- Human Security Report Project. The decline in global violence: evidence, explanation, and contestation. Simon Fraser University, Canada. 2013. Viewed October 21, 2016; Uppsala Conflict Data Program. UCDP Battle-Related Deaths Dataset v.5-2016. Uppsala University. Viewed October 21, 2016.

- United Nations Division for the Advancement of Women, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sexual Violence and Armed Conflict: United Nations Response. April 1998. Viewed October 21, 2016.

- Tucker JB. War of Nerves: Chemical Warfare from World War I to Al-Qaeda. New York: Pantheon Books, 2006.

- Falk J. The health impacts of war and armed conflict. Medact. November 20, 2015. Viewed October 21, 2016; World Health Organization. Potential impact of conflict on health in Iraq. March 2003. Viewed October 21, 2016; Murray CJL et al. Armed conflict as a public health problem. BMJ. 2002 Feb 9;324(7333):346-9; Sidel VW, Levy BS. The health impact of war. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion. 2008:15(4);189-195; Steel Z et al. Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009 Aug 5;302(5):537-49. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1132..

- Health Knowledge. Migration and the Health Effects of International Trade. Public Health Action Support Team. 2011. Viewed October 21, 2016.

- Health Knowledge. Migration and the Health Effects of International Trade. Public Health Action Support Team. 2011. Viewed October 21, 2016; Abbot A. The mental-health crisis among migrants. Nature. 2016 Oct 13;538:158-160.

- World Health Organization. Tuberculosis: Global map of TB. Viewed October 23, 2016.

- Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. Infectious diseases key cause of U.S. deaths until 1920s. December 4, 2013. Viewed October 22, 2016.

- World Health Organizationn. The top 10 causes of death. Viewed October 22, 2016.

- Geddes L. Tuberculosis now leading cause of death from infectious disease. New Scientist. October 28, 2015, Viewed October 22, 2016.

- Alsan MM et al. Poverty, global health and infectious disease: lessons from Haiti and Rwanda. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 2011 Sep; 25(3): 611-622.

- Katona P, Katona-Apte J. The interaction between nutrition and infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008 May 15;46(10):1582-8.

- Feingold BJ et al. A niche for infectious disease in environmental health: rethinking the toxicological paradigm. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2010 Aug;118(8):1165-72; NIEHS Superfund Research Program. The Interplay between Environmental Exposures and Infectious Agents: Session I – Introduction to Infectious Agents and Their Interactions with Environmental Exposures. Viewed October 30, 2016.

- Johnson R, Jelmayer R. Brazil to allow aircraft to spray for mosquitoes to combat Zika. Wall Street Journal. July 1, 2016. Viewed November 1, 2016; Sanchez R, Goldschmidt D, Scutti S. Zika spraying in Miami: what you need to know. CNN. September 9, 2016. Viewed November 1, 2016.

- Nowogrodzki A. Bees die needlessly as Zika prompts US state to spray pesticide. New Scientist. September 2, 2016. Viewed October 30, 2016.

- Khamsi R. Mystery illness devastates honeybee colonies. New Scientist. February 14, 2007. Viewed October 30, 2016.

- Friel LA. Infectious disease in pregnancy. Merck Manual. December 2014. Viewed October 22, 2016; Zare Mehrjardi M, Keshavarz E, Poretti A, Hazin AN. Neuroimaging findings of Zika virus infection: a review article. Japanese Journal of Radiology. 2016 Oct 6. [Epub ahead of print]; Gomez Licon A. Zika syndrome: health problems mount as babies turn 1. Associated Press. October 11, 2016. Viewed October 22, 201; Bayless NL. Zika virus infection induces cranial neural crest cells to produce cytokines at levels detrimental for neurogenesis. Cell Host & Microbe. 2016 Oct 12;20(4):423-428.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Basic Facts: Definition of a pandemic. 2012. Viewed October 22, 2016; World Health Organization. Health topics: Infectious disease. Viewed October 22, 2016.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Basic Facts: Definition of a pandemic. 2012. Viewed October 22, 2016; World Health Organization. Health topics: Infectious disease. Viewed October 22, 2016.

- FLU.gov. Pandemic awareness: About pandemics. US Department of Health & Human Services. Viewed October 22, 2016.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Basic Facts: Historical pandemics. Viewed October 22, 2016; FLU.gov. Pandemic flu history. US Department of Health & Human Services. Viewed October 22, 2016.

- Media centre. Influenza (seasonal). World Health Organization. 2014. Viewed October 22, 2016.

- FLU.gov. About the flu: How the flu virus changes. US Department of Health & Human Services. Viewed October 22, 2016.

- World Health Organization. Ebola virus disease. January 2016. Viewed October 23, 2016.

- World Health Organization Ebola Virus Disease: Situation Report. June 10, 2016. Viewed October 23, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smallpox. July 12, 2017. Viewed May 16, 2023.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Plague: Frequently Asked Questions. September 14, 2015. Viewed October 23, 2016

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Plague: Frequently Asked Questions. September 14, 2015. Viewed October 23, 2016

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Plague: Frequently Asked Questions. September 14, 2015. Viewed October 23, 2016; Benedictow OJ. The Black Death: the greatest catastrophe ever. History Today. Volume 55; March 3, 2005. Viewed October 23, 2016.

- Institute of Medicine. Health and the Environment in the Southeastern United States: Rebuilding the Unity. Workshop Summary. Chapter Four. Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 2002.

- de Vries S, Verheij RA. Natural environments—healthy environments? An exploratory analysis of the relationship between greenspace and health. Environment and Planning A. 2003 Oct; 35(10): 1717-1731; Maas J et al. Green space, urbanity, and health: how strong is the relation? Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2006 Jul; 60(7): 587-592.

- Institute of Medicine. Health and the Environment in the Southeastern United States: Rebuilding the Unity. Workshop Summary. Chapter Four. Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 2002; de Vries S, Verheij RA. Natural environments—healthy environments? An exploratory analysis of the relationship between greenspace and health. Environment and Planning A. 2003 Oct; 35(10): 1717-1731.

- Ecosystem Services Team. Health and wellness benefits of spending time in nature. US Department of Agriculture, Viewed October 31, 2016.

- Ecosystem Services Team. Health and wellness benefits of spending time in nature. US Department of Agriculture, Viewed October 31, 2016.

- Strife S, Downey L. Childhood development and access to nature: a new direction for environmental inequality research. Organization & Environment. 2009 Mar; 22(1): 99-122.

- Strife S, Downey L. Childhood development and access to nature: a new direction for environmental inequality research. Organization & Environment. 2009 Mar; 22(1): 99-122.

- Children & Nature Network. Tools & Resources: Infographics. Benefits of nature. Viewed October 31, 2016.

- Children & Nature Network. Tools & Resources: Infographics. Benefits of nature. Viewed October 31, 2016.

- World Wildlife Fund. Living Planet Report 2016: Risk and resilience in a new era. Switzerland: World Wildlife Fund International, 2016. Viewed November 1, 2016; Center for Biological Diversity. The Extinction Crisis. Viewed November 1, 2016.

- World Wildlife Fund. Living Planet Report 2016: Risk and resilience in a new era. Switzerland: World Wildlife Fund International, 2016. Viewed November 1, 2016.

- Institute of Medicine. Health and the Environment in the Southeastern United States: Rebuilding the Unity. Workshop Summary. Chapter Four. Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 2002.

View All Footnotes

Source: https://gardencourte.com

Categories: Outdoor