These days, the biggest stars—like Miley Cyrus and Beyoncé—know the easiest way to get the world to gawk is to chop off your long locks for a “boy cut.” And then, perhaps, perform some sexually provocative dance moves on TV.

You are watching: Untangling the Tale of the Seven Sutherland Sisters and Their 37 Feet of Hair

“Their antics and wild, over-the-top parties were the talk of Niagara County.”

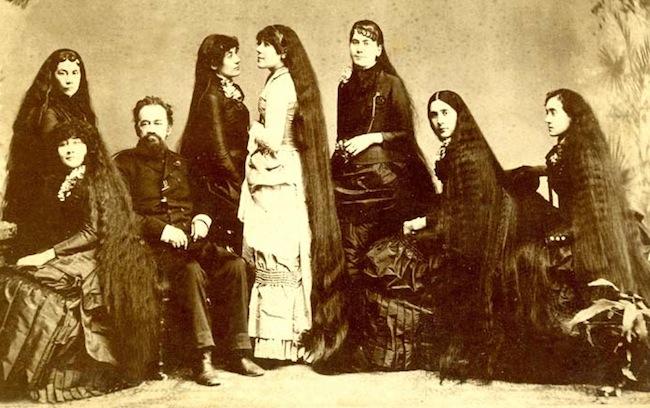

In the late 19th century, though, the most startling, erotic thing you could do as a stage performer is let down your Rapunzel-esque floor-length hair. In fact, according to their biographer, the first real celebrity models in the United States were known as the Seven Sutherland Sisters, who had 37 feet of hair among them. Sarah, Victoria, Isabella, Grace, Naomi, Dora, and Mary Sutherland sang and played instruments—but no one really cared about that. No, the crowd came to ogle their magical, mythical, uber-feminine hair.

Flaunting all that awesome hair onstage wasn’t quite enough to launch the Sutherlands from abject poverty to riches, so the sisters’ father, the Rev. Fletcher Sutherland, concocted a patent hair-growing tonic. Because Victorian women coveted the sister’s luscious locks, the cash came flooding in. The family grew rich beyond its wildest imaginations, as the sisters knocked serious political issues off the newspapers’ front page with their outrageous celebrity antics. By the mid-1880s, none of the sisters could walk down the street, their flowing tresses dragging behind them like dress trains, without being mobbed by starstruck fans.

Theirs was a true Cinderella story. The sisters—born sometime between 1845 and 1865—lived a hardscrabble life as drudges on their family’s turkey farm in Cambria, New York, in Niagara County, according to Arch Merrill’s 1966 book, “Shadows on the Wall: Tales of New York State.” They shepherded turkeys barefoot in shabby clothes, and to make matters worse, their mother, Mary, would slather their long hair with a horrible smelling ointment she believed would make it grow thick and strong. The girls’ classmates shunned them for the odor. Embarrassed, the young girls with the long, thick braids would hide in the tall grass when visitors approached their log cabin.

Meanwhile, their lazy father, Fletcher Sutherland, preoccupied himself proselytizing and politicking. The farm had been established by their grandfather, Col. Andrew Sutherland, an inventor who was esteemed for his role in the War of 1812. A preacher, politician, inventor, writer, and all-around smoothing-talking showman, Fletcher once worked for President James Buchanan, and nearly got himself murdered for opposing the Civil War.

On the farm, the Sutherlands probably had no idea that the country was on the verge of a tremendous Industrial Revolution, led by entrepreneurs in Buffalo and Niagara Falls, soon to be centers of invention and electrical power, just 20 miles down the road from their home. But Fletcher always had more hopes for his children than a life of tending turkeys. When they were little, he started showcasing his daughters’ singing abilities at church.

The girls’ mother died in 1867, when the youngest, Mary, was just a toddler, and the sisters were freed from the foul-smelling oil. After her death, Fletcher was only more determined to pursue his dreams of fame and fortune by exploiting his kids. The Sutherland children, including the girls’ only brother, Charles, started to pick up musical instruments and tour churches, fairs, and community theaters around Niagara County as the “Sutherland Concert of Seven Sisters, and one Brother.” At age 13, the fifth daughter, Naomi, especially wowed audiences with her mellifluous bass singing voice and waist-long hair, and she received positive reviews in the Rochester and Albion newspapers.

“Each subsequent death in the family made the sisters more and more heartbroken.”

Billed as “The Seven Wonders,” the Sutherland sisters, now performing without Charles, made it to New York City in early December 1880, where their act and impressive tresses made their Broadway debut. In summer 1881, the Seven Sutherland Sisters took their show on the road, touring the South, hitting cities like Pensacola, Florida; Mobile, Alabama; and New Orleans before landing at the first World’s Fair in the South, the International Cotton Exposition, in Atlanta, Georgia, in fall 1881. Everywhere they went, audiences would audibly gasp when the young women unleashed their locks, shimmering under the gaslights.

Victorian women pined to have such transfixing hair. At a time when disease and bad medicine caused men and women’s hair to fall out, extremely long and thick hair became the ultimate symbol of femininity, thought to almost have magical powers. According to mythology and the literary greats of the time like Browning, Dickens, Thackeray, and Yeats, floor-length locks could mask nudity, rope in a male suitor, give him a cozy shelter, or smother him in bed.

Sarah, the oldest Sutherland sister, only had 3 feet of thick, wavy hair, the shortest hair of the group. But when the sisters posed for photo shoots, generally, Sarah would sit and others would bend their waists so that it seemed that all seven had hair that brushed the ground. Victoria had the longest, a full 7 feet from the top of her head to the ends. When she let it down, it would drag behind her. Naomi’s braid was four inches thick, and when it was undone, she could cover her whole body with her magnificent mane, which was 5½ feet long. Mary, the youngest, was mentally unstable her whole life, and some doctors and preachers went as far as blaming her 6 feet of very heavy, dark hair for pulling on her head.

Read more : Substitute for Maple Syrup

Aside from their intoxicating hair that envious fans would sometimes try to cut and steal, their number, seven—considered a holy, biblical number—ascribed another level of mysticism to their act. Agents came knocking, as did the moguls of the vaudeville and circus circuit. By 1882, the sisters signed a deal to tour with with W.W. Coles Colossal Shows, and by 1884, the sisters had joined Barnum and Bailey’s Greatest Show on Earth as a sideshow attraction. P.T. Barnum himself dubbed them, “the seven most pleasing wonders of the world.”

Brandon Stickney, an upstate New York journalist who published “The Amazing Seven Sutherland Sisters: A Biography of America’s First Celebrity Models” in 2012, explains on the Sideshow World site that each sister from this warm, generous family had a distinct personality.

“A leather-covered Bible her constant companion,” Stickney writes, the first-born “Sarah used her talents as a high solo soprano and pianist to become a revered music teacher. A mezzo-soprano, Victoria, the second sister, boasted diamonds on her fingers and gold on her neck. With dark eyes like her younger brother, the baritone Charles Sutherland, the third sister, Isabella, [was] a rich tenor, poet, dreamer and tragically lost heart [who] rejected religion and clung to untamable men.

“The fourth sister, chatty Grace, an alto singer, was the great communicator, managing most business and personal correspondence. Busty and irreverent, Naomi, the fifth sister, sported the sly smile of Grace and a Roman nose on her plump face. The most startlingly attractive of the sisters, Dora, the sixth by birth, [who] had the face of a dreamy 19th century pinup, a turned up nose and a sentimental pout that could melt any heart. Though her smoky moon face, deep eyes and full lips were remarkable, Mary, the family felt, was sometimes best understood from a distance—her stage talent fleeting, alto singing unreliable, and numerous tantrums baffling.”

Even though they were with Barnum and Bailey’s, the Seven Sutherland Sisters set themselves apart from circus folk and sideshow freaks, who were reviled by polite society. They were elevated by their goddess-like status and their refined, tasteful act, which involved engaging, articulate stories, church music, and drawing-room songs. Middle-class Americans considered their show dignified and enlightening.

The sisters, obviously, were a runaway success. But the stage income must not have been enough for Fletcher, who started toying with the idea of a hair-growing tonic in 1882, based on the late mother Mary’s foul-smelling ointment. He claimed that he created his concoction to reverse and prevent his own balding process, but it’s likely that it was a sham and he just wanted to capitalize on his daughter’s stunning tresses. But according to Rapunzel’s Delight, Fletcher’s presumably less-odious hair tonic didn’t catch on until he joined forces with Harry Bailey (born J. Henry), a relative of circus magnate James A. Bailey, who was also courting Naomi. Bailey founded the Sutherland Sisters Corporation and applied for the company’s first trademark in 1883, for the Seven Sutherland Sisters Hair Grower. Then he set about to market the stuffing out of it.

Meanwhile, Fletcher Sutherland sent the liquid remedy to a chemist, who gave it a glowing review: “Cincinnati, Ohio, March, 1884: Having made a Chemical Analysis of the Hair Grower prepared by the Seven Long Haired Sisters, I hereby certify that I found it free from all injurious substances. It is beyond question the best preparation for the hair ever made and I cheerfully endorse it. — J.R. Duff, M.D., Chemist.”

By the end of 1884, the Sutherland Sisters Corporation had garnered $90,000 in sales, reports Douglas Farley of the Erie Canal Discovery Center. (In 1885, Harry Bailey and Naomi Sutherland were married, and the couple had three children before Naomi’s death in 1893.) Fletcher died around 1888, and the sisters themselves became part-owners in the company, which expanded to include a whole line of hair products including a comb, a scalp cleanser, and eight shades of “Colorators,” as well as other cosmetics like face cream.

According to Hair Raising Stories, the academic journal The Pharmaceutical Era analyzed the Hair Grower (also sold as Hair Fertilizer) and published its findings in 1893. The tincture was made up of 56 percent witch-hazel water, 44 percent bay rum, and a little bit of salt, magnesia, and hydrochloric acid, which removed the yellow color the chemical would naturally produce. According to Bailey’s patent petition, the Scalp Cleaner powder had “borax, salt, quinine, cantharides, bay rum, glycerine, rose water, alcohol, and soap,” which is more or less what a 1907 examination concluded, research on Peachridge Glass reveals.

These preparations were not cheap, going for anywhere between $.50 and $1.50 a jar, which could be a day to nearly a whole week’s salary for Americans in the 1880s. A savvy marketing scheme only increased the Sister’s high-class image, as the products were targeted to well-to-do society women. The middle-class ladies, meanwhile, took it to mean that the claims the packaging made were valid. Aside from an endorsement from the Sisters, the packages were often labeled with “Rev. Fletcher Sutherland,” his preacher title giving their wares even more credibility.

In an era when women were expected to be frail, delicate housewives, the Sutherlands proved themselves ambitious businesswomen. They came up with clever ad slogans such as “A woman’s hair is her crowning glory” and “Remember ladies, it’s the hair, not the hat, that makes you beautiful.” When they weren’t touring with Barnum’s or selling out concert halls, the sisters still traveled the world, promoting their products as live hair models in the windows of drug stores and hotel lobbies for hours at a time, always drawing crowds. In New York City, the street grew so jammed with fans it stopped traffic, and the Sutherlands were banned from modeling in windows there. The sisters also doled out beauty advice, and had to keep up with the latest news in hair fashion.

Eventually, the company opened offices in New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Toronto, and even Havana, Cuba, to manage its vast network of 28,000 dealers. By 1890, the sisters had sold 2.5 million bottles of the Hair Grower alone, raking in more the $3 million dollars. And while they were obviously considered Gibson Girl-esque ideals of feminine sexuality, Sarah, Grace, Dora, and Mary never married, possibly for fear that a husband could take controlling interest of their wealth.

According to Stickney, the Sutherland women achieved such “It Girl” status, they dominated the front page of newspapers, knocking U.S. presidents like Rutherford B. Hayes and William Howard Taft below the fold. Hair historian Bill Severn said, “Everything they did was news and for years their hair made Sutherland a household name.” Besides the gossip cycle, features on the Sutherlands appeared in The New Yorker, Time, The New York Times, Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, Harper’s, McClure’s, Cosmopolitan, and Reader’s Digest.

Read more : Essential Oil Blends for Men

Poems, prose, and stage plays all furthered their legend. Of course, at the height of their popularity, Sutherland Sister memorabilia became instantly collectible, as concert programs, photos, calling cards, and postcards of the women would be framed, particularly when they were autographed. But the obsession with getting a piece of the septet’s hair got creepy, too. According to Stickney, one fan is said to have offered Victoria $2,500 to cut off all her hair. “She refused that offer, but sold one strand of hair to a jeweler for $25,” he writes. “The jeweler suspended the hair in his shop window with a seven carat diamond at the end.”

Not surprisingly, the meteoric rise to fame and riches made a deep impact on the family, which grew increasingly eccentric as the once-impoverished sisters reveled in their lavish wealth. In 1893, the seven, now world-famous, returned home determined to live together, erecting a tremendous mansion in rural Cambria, New York, where their family’s log cabin once stood. The 14-room dream home—which also became the headquarters of their business—looked something like a princess’s castle with a turret, cupola, and veranda. Inside, the family and their guests luxuriated with all-hardwood floors under their feet, heavy crystal chandeliers overhead, and black walnut woodwork all around them. The opulent estate featured the first indoor bathroom in Cambria, a marble beauty with hot and cold running water, as well as beds imported from Europe. Even the servants had posh, well-appointed rooms in the attic.

Writing in the April 1982 edition of Yankee magazine, Dianne L. Sammarco and Kathleen L. Rounds explain that “Pets were treated like royalty, with winter and summer wardrobes, and grand funerals and obituaries in the local newspapers. The carriage horses were shod in gold. The sisters sponsored many a gala social for the neighbors, often including fireworks.” To maintain their impressive running-water system, a servant had to fill a tank in the attic with water every day.

Using loose strands that came out when their hair was brushed, the sisters had seven 3-feet-tall mannequin dolls made in their image, according to Long Hair Lovers Blog. Dressed in the best Victorian fineries, the dolls would be sent to stores to advertise Seven Sutherland Sisters products in the store windows, but were always returned to the manse, in the charge of the women’s seven personal maids, who were also paid to comb and detangle the sisters’ flowing locks every night.

Even though they were raking in millions at the turn of the century, the women’s spending on such extravagances—servants, clothes, fine jewelry, seconds homes, globe-trotting, booze, and lovers—was out of control. Outwardly, they maintained the appearances of proper, educated Christians, but behind closed doors, they engaged in love triangles, in-fighting, drug use, and bad financial investments. Their antics and wild, over-the-top parties were the talk of Niagara County, as people speculated about whether they were polyamorous or practicing spiritualism or witchcraft.

“Everywhere they went, audiences would audibly gasp when the young women unleashed their locks, shimmering under the gaslights.”

Naomi barely got to enjoy the spoils of their outlandish life in the mansion—she died before age 40 in 1893, the year the home was completed. Her death shook the sisters to the core. The family planned to invest $30,000 in a mausoleum, but it never came to be, reports Susan Tobias in her 2012 Plattsburgh, NY, Press Republican article. As the sisters were still touring with Barnum’s, and continued to do so until 1907, the group quickly auditioned for her replacement, and chose Anna Louise Roberts, a woman from Carbondale, Pennsylvania, who had 9 feet of hair. Each subsequent death in the family made the sisters more and more heartbroken. They even invested $500 to have a full-on funeral with a casket, flowers, and crepe on the door when a beloved dog passed away.

A young French nobleman by the name of Frederick Castlemaine came around to court the lovely Dora, but ended up marrying 40-something Isabella, who was more than 10 years his senior. According to the Yankee article, the dashing rogue “had a few eccentricities of his own, like addictions to opium and morphine, and the unnerving hobby of shooting the spokes out of wagon wheels from his seat on the Sutherlands’ front porch. Impressive though his marksmanship may have been, local farmers were unhappy with this practice. He salved their indignation with handsome payments. In 1897, while accompanying the sisters on one of their tours, Castlemaine committed suicide.”

The sisters didn’t have Castlemaine embalmed right away. Instead, they put his body in a glass case, which they would visit and sing to on a daily basis. After 10 days the smell got so troubling, local health officials stepped in and forced the family to bury him in his mausoleum in Glenwood Cemetery in Lockport, NY, where most of the Sutherland sisters ended up after they died. Isabella couldn’t get over it for two years, and talked to him at his grave every night until she met Alonzo Swain, the second much-younger man she married.

Victoria, ever the beauty, finally married a 19-year-old man when she was 50. This outraged her sisters, who kicked her out of the mansion and ostracized her for the rest of her short life; she passed away at 53 in 1902. A woman with 6 feet of hair, Anna Haney, was hired as her replacement. Meanwhile, mentally unwell Mary got increasingly antisocial, and when she threatened her family with spells, her sisters would lock her in her room. When the bandleader Sarah died in 1919, the family, once again, kept her body on display in the home, and resisted burying her.

The final death knell to the Sutherlands’ prosperity came in the 1910s: Rebellious young women, known as flappers, started to chop their hair into startlingly short bobs. As the trend grew more mainstream, the appeal of the Seven Sutherland Sisters Hair Grower plunged. Isabella died in 1914, and the family fortune was slipping away fast. The last three women headed to Los Angeles in 1919 in a desperate attempt to pitch their story to Hollywood, but they deal went sour and Dora was killed in a car crash during their trip. Mary and Grace were so broke at that point, they didn’t even have the money to get her cremated, so they never claimed her remains.

By 1920, these two were the only living sisters, and they attempted to keep their “hair fertilizer” business alive in an era that no longer loved ridiculously long locks. Hardly able to buy food, they had to abandon their mansion in 1931. Great Jazz Age cartoonist John Held, Jr., gently mocked them as “Dream Girls of a Dim Decade.” By 1936, the Seven Sutherland Sisters went out of business for good. The empty estate caught on fire and burned to the ground on January 24, 1938, and endless numbers of Seven Sutherland Sisters documents—including, possibly, the patent tonic recipes—and artifacts went up in smoke. Mary ended up committed to Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane, where she died in 1939. Grace died destitute at age 92 in 1946, and as there was no room for her in the Castlemaine mausoleum, she was buried in an unmarked grave.

And so the seven headline-stealing wonders of the Victorian era faded into obscurity. Perhaps we can rest assured that Miley Cyrus and her twerking shenanigans will disappear deep into the pages of pop-culture history in much the same way. One can always hope.

(Recommended reading: Brandon Stickney’s book “The Amazing Seven Sutherland Sisters: A Biography of America’s First Celebrity Models”; Clarence Lewis’ book “The Seven Sutherland Sisters”; Stickney’s article on the sisters in Sideshow World; the site’s adaptation of Arch Merrill’s research and their reprint of a 1947 “American Weekly” article,“Strange Stories of the Sutherland Sisters”; Susan Tobias’ “Press Republican” article; Ferdinand Meyer V’s post on the sisters at Peachridge Glass; and web pages devoted to the Seven Sutherland Sisters at Hair Raising Stories and Rapunzel’s Delight. If you buy something through a link in this article, Collectors Weekly may get a share of the sale. Learn more.)

Source: https://gardencourte.com

Categories: Recipe