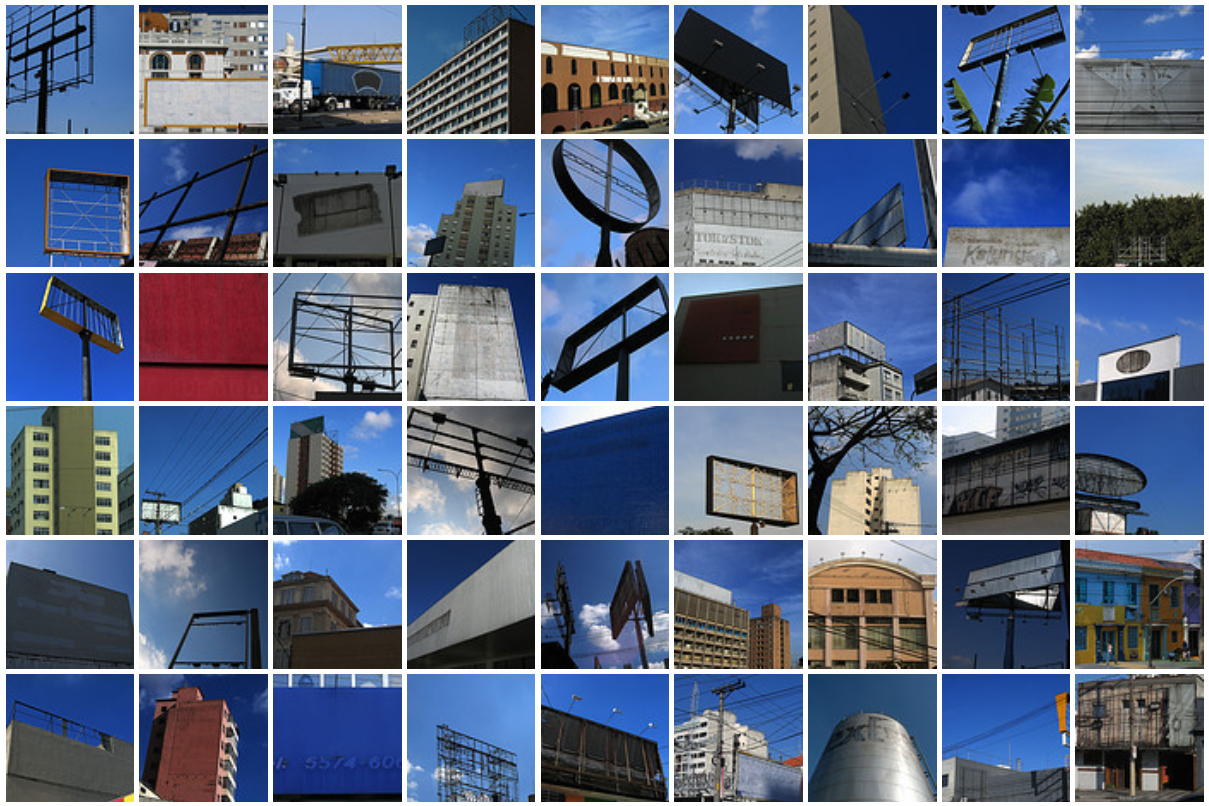

When São Paulo introduced its Clean City Law (Lei Cidade Limpa) a decade ago, over 15,000 marketing billboards were taken down. An additional 300,000 ostentatious business signs, hanging over streets or painted in large letters on facades, were also subject to a hefty fine if they were not removed promptly. Bus, taxi, and poster advertisements had to go as well. Even handing out pamphlets on the street was prohibited. While this legislation helped clean up the largest city in Brazil, it also revealed surprises hiding behind ad-covered urban signs and surfaces.

The move to ban ads in this giant metropolis was controversial, in part due to its substantial estimated impact on the local economy. The law was (predictably) fought at all stages by business groups with a vested commercial interest in buying and selling prime public ad space.

You are watching: Clean City Law: Secrets of São Paulo Uncovered by Outdoor Advertising Ban

Some arguments from the business community were framed as selfless. A lack of ads, according to one such argument, would lead to less lighting (of billboards and walls) and thus more dangerous streets. Other arguments were more blatantly self-interested. Clear Channel Outdoor, one of the world’s biggest outdoor-advertising companies, went so far as to sue the city, claiming the ban was unconstitutional.

In the end, the law went into effect on January 1st, 2007, and businesses were given 90 days to comply or pay the price.

Read more : Nine Important Things About the Cat Palm

Most citizens were fans of the initiative, including local reporter Vinicius Galvao, who writes for the Folha de São Paulo, Brazil’s largest newspaper. He notes that his hometown is “a very vertical city,” but before the law “you couldn’t even [see] the architecture of the old buildings, because they were just covered with billboards and logos and propaganda. And there was no criteria [to restrict them].”

While the law had broad public support, some residents were worried for financial, pragmatic, and aesthetic reasons. For starters, the city would not only lose revenue from absent ads, but would have to actively spend money taking down the resulting ghost town of empty billboards. Further: signs, no matter how corporate, can be wayfinding devices, and stripping them could make familiar routes harder to follow. Other critics were nervous that without the colorful veneer of advertisements the urban environment might look worse rather than better, unmasked as a gloomy concrete cityscape. Passing the Clean City Law did uncover a number of things no one expected, for better and worse.

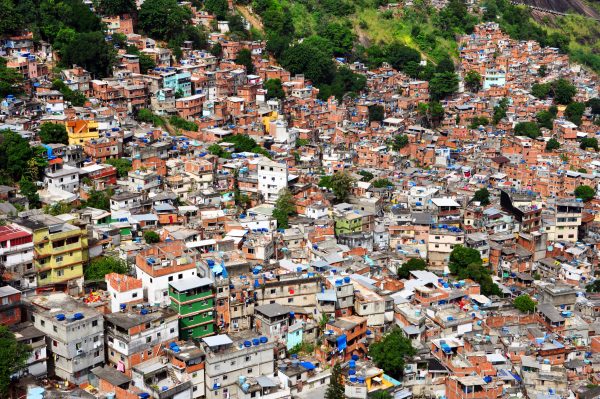

As it turned out, advertisements were quite literally covering up problems with the city that needed to be addressed. Removing billboards revealed, for instance, the presence of certain smaller shanty towns (known as favelas) that few knew existed, hidden as they were behind a vertical landscape of giant signs. As facade-spanning ads were pulled down from the sides of buildings, immigrants living inside of the same factories in which they worked (often in poor conditions) were discovered. Crumbling civic infrastructure was also cast into the spotlight, made more visible in the absence of distracting ads.

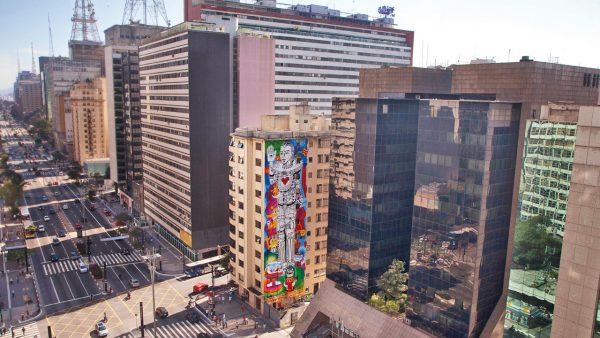

Cleaning up ads from the sides of buildings also inadvertently freed up more space for street artists to work with, and helped make new and existing artworks stand out against the urban environment.

Enthusiastic city workers, however, took things a step further than people expected when it first came to enforcing the law. Certain public murals were wiped clean, causing concern among citizens. The removal of one 2,000-foot-long work in particular sparked local outrage as well as global press coverage. Eventually, with public support, the city created an official registry to protect key extant and future pieces of street art, now more visible than ever.

Read more : Pruning In The Garden – Do You Have To Prune Garden Plants

The Clean City law also forced building owners and businesses to confront unpainted and unattractive architecture, reconsidering their visual presence in shared civic spaces. For businesses forced to remove their prominent signs and logos, painting structures in distinctive colors became a way to help people identify and distinguish between them.

This move to reduce advertising in public spaces is not unique to São Paulo, though other cities rarely take it so far. Above, the London Trocadero is shown first in its original condition, then during its prime marketing career and, finally, after the advertisements were removed once again. Several states in the US prohibit billboard advertising, including Alaska, Hawaii, Maine and Vermont. In Beijing, the mayor banned public ads for luxury apartments for encouraging self-centered and over-indulgent lifestyles. Paris has recently reduced public ad space by a third, while Tehran temporarily replaced its 1,500 advertising billboards with art for 10 days in 2015.

Today, some ads are being reintroduced in São Paulo, but in a much more controlled fashion than before. An interactive search engine ad at bus stops, for instance, helpfully allows residents to look up weather conditions for their destinations, providing a useful service.

Starting from scratch has its advantages, like letting the community drive decisions about what to allow and what to prohibit. As São Paulo’s approach illustrates, such a sweeping initial act of removing ads can reveal both secret weaknesses but also hidden strengths of a city.

Update: this article formed the basis for a story in The 99% Invisible City!

Source: https://gardencourte.com

Categories: Outdoor